Jules Dietz worked for Muller Martini for 32 years – most recently as Regional Sales Director for Africa and Switzerland. He is retiring at the end of April. In a personal blog, the engineer looks back on his interesting professional life in the graphic arts industry. He tells you what is special about machine projects for African customers and what plans he has for the third phase of his life.

At the end of April, I'll be coming full circle. From 1975 to 1979, I completed an apprenticeship at Muller Martini in Zofingen as a machine mechanic specializing in electrical engineering. After that, I worked briefly in control engineering at what was then Grapha Electronic. My further professional career took me to various companies. I was employed as a test engineer at Patvag-Technik AG and produced the first samples for the airbag igniter for Mercedes Benz AG. Later, I was responsible for the OEM business at Strapex AG and at the large company Ascom, which had 16,000 employees at the time, in the service automation sector for markets in Italy, Australia and Southeast Asia, among others.

Travel in the genes

I returned to Muller Martini in 1995 and over the years continued my education in various directions (NKS Management School/Management Methods, ZfU Marketing Seminar/Capital Investments, postgraduate studies in Business Administration). It's true that my father also worked at Muller Martini in Zofingen for almost four decades – first as a machine fitter, then as a machine instructor. Nevertheless, my path into the graphic arts industry was not necessarily preordained. As a child, I spent a lot of time on the farm of a schoolmate, which is why I could well imagine becoming a farmer one day. In the end, however, I was more interested in technology and machines.

Since I speak Italian as well as German, French and English, Italy, but above all Southeast Asia and Australia, were my first destinations – at that time with our contract partner Heidelberg/EAC. Because my father traveled abroad a lot and for a long time during my youth (which was much more drastic then than nowadays), I didn't really want to travel that much. But our industry in Switzerland is export-oriented – and I obviously had traveling in my genes

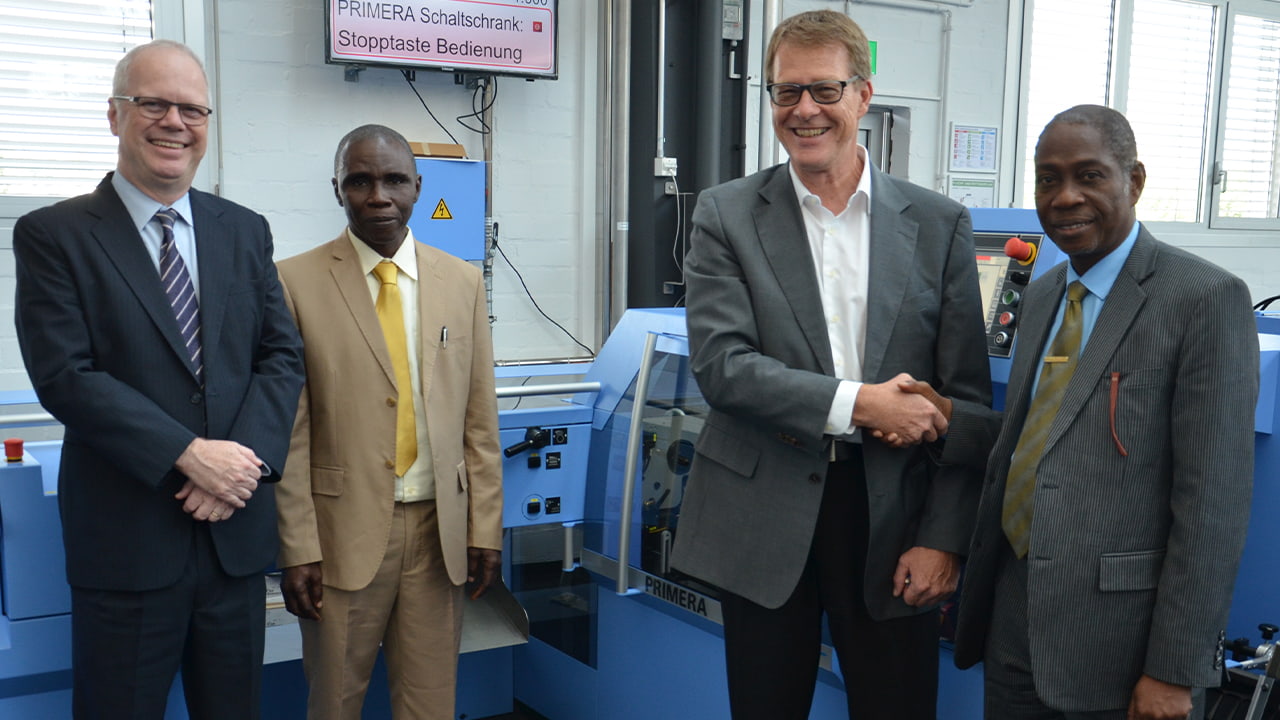

.jpg) For Muller Martini in South Africa

For Muller Martini in South Africa

How I became the sales manager for Africa also has a lot to do with traveling. In 2005 – after having made a few smaller motorcycle trips to the Tunisian Sahara in the years before – I planned a seven-week trip through southern Africa together with my wife. During the preparation phase I also had contact with the company

Thunderbolt, our representative in South Africa. A position as sales manager for Muller Martini had just become available there. I applied for it, got it promptly and emigrated to South Africa together with my wife.

The three years in South Africa were an intensive time with a lot of new things. Entering another country, finding an apartment, insurance, registering a car and opening a bank account were all associated with some difficulties for me as a foreigner. Dealing with a completely new culture as well as a high crime rate was also unfamiliar. Every time I left the house, I had to arm the alarm system. Before I drove back to the garage, I had to make sure no one was following me. On the other hand, South Africans are extremely friendly and helpful. Therefore, it was not always easy to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Accepting the cultural differences

As a Swiss, one likes to take weekend trips to the nearby mountains. In South Africa, however, the mountains – or rather hills – were often 200 to 300 kilometers away. To get there, we always traveled by 4x4 car and slept in lodges. What we found most impressive were the visits to the large game parks, where we could observe lions, hyenas, elephants, zebras and many other animals in the wild life – simply wonderful.

Before drupa 2008, the Board of Directors of Muller Martini decided to coordinate machine sales for the entire African continent via a Sales Manager from Switzerland. I got this job, returned to Switzerland and worked from headquarters for the whole of Africa until I retired.

If you want to sell machines successfully in Africa, you have to learn to understand the customers there and accept the cultural differences. In addition, you have to be able to sound out the financial and technical possibilities of the customers in the project phase and know (or at least guess) how great the know-how of the operators is. If you take all these points into account, you can build and implement solutions that are more in line with requirements.

Core products textbooks and exercise books

The graphic arts industry in Africa is strongly focused on the core products of textbooks and exercise books. Print runs for textbooks in most countries are in the double-digit millions. South Africa alone has an annual demand of 35 to 60 million textbooks. Historically, the durability of books is – or rather was – a major issue. That's why many South African bookbinders today use PUR on their perfect binders. Consumer magazines and high-circulation newspapers are almost unique to South Africa.

There are big differences between the individual countries in terms of production, quality and logistics. This is also partly due to the advice given. Presses are sold that don't meet the requirements or bookbinding lines that are not configured for the popular products. I know print shops that have bought a four-color press for the school book sector. The bottom line is that for each run, the sheets have to go through the press twice in order to print four colors on both the front and the back.

Many state-owned print shops

South Africa is the leading market on the continent in many areas. As a result, Muller Martini has a large installed base of mailroom equipment, saddle stitchers and perfect binders there. The government printing plant in Pretoria produces passports with the same security features as in the major industrialized nations. A few years ago, the digital printing market also got off to a successful start. Many print products are exported from South Africa to other African countries. The Maghreb zone with Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco is also a good market for Muller Martini. So is East Africa, where we recently sold a Vareo PRO perfect binder in Tanzania and an Alegro line for textbooks in Ethiopia, and recently sold an Alegro line for exercise books to Morocco.

A particular challenge is that many African countries operate state-owned printing plants for the textbook sector. Private companies play only a secondary role in this segment. In the case of state-owned print shops, projects for new presses have to be offered by means of a bidding process. It is often very difficult and a great challenge to take the required functions and performance into account. This is because the different specifications of machines make comparability difficult or even impossible. Private companies can buy machines on the open market, but (unfortunately) sometimes they do so as second or third hand equipment.

Fewer investments in recent times

Running a print shop already costs money in normal times. If rising oil and paper prices or the corona pandemic also affect the markets, this naturally has a negative impact on many print shops. In addition, the level of technology is constantly rising. This is why there has been less investment in Africa recently. This in turn means that more (school) books have to be imported. A lot is produced for Africa in the Middle East, India or China. Even when the UN promotes education, printing companies in Europe, USA, Canada or Italy often produce textbooks for the "donor". Looking at the positive side: I see potential for new graphic equipment behind the development backlog – in both the conventional and digital sectors.

The number of print shops with business models in digital printing is increasing. They recognize the advantages in job handling when the job goes from the computer directly to the press, thus eliminating the time-consuming chemical-technical process of making printing plates.

.jpg) Many old machines in use

Many old machines in use

"What are the biggest challenges facing the graphic arts industry in Africa?" my (sales) colleagues often ask me. We are dealing with a market in which some very old machines are in use that are difficult to maintain. For larger investments, however, there is often a lack of money and specialists to operate the equipment. For us – as for other machine manufacturers – the problem is that we can hardly support these old systems. For this reason, African companies often use their own (service) resources for old machines. All in all, it remains a market with its own dynamics.

Which brings me to the topic of service. Indeed, after-sales service is a major challenge – currently not only in terms of supply chains for spare parts, but also in terms of our African customers' know-how about old machines. The knowledge of production processes – I'm thinking in particular of perfect binding – is also at a rather low level. Technical support and training are therefore a big issue. However, sending technicians from our plant for an on-site assignment often fails because of the costs. And in the case of remote contracts, the fees often act as a deterrent, because the companies do not see the (immediate) benefit – and the older machines allow a remote connection at all!

That's why, with new equipment, it's especially important to have the customer on board from the start on and provide him with all the relevant information during installation. He must also be in control of the daily service and maintenance of the plant in the long term.

Agents as antennae to the customer

Local agents work for Muller Martini in all African countries. These reflect the potential of the market. For us, they are the antennae to the customer in the respective cultural area. They are importers for spare parts, they coordinate our operations, and they are something like the advocate for the customer to Muller Martini. For me, the agents are good conversational partners, and I have to travel less to keep my ear to the market.

The agents get in touch with me when they have a project. Or I explain plant concepts that can trigger projects. The customer's requirements, the agent's understanding of the market, my background knowledge regarding machine portfolios, and input from colleagues ideally lead to a solution that we present to the customer together. However, one must always be aware that – as mentioned earlier – there may be a tender that dilutes a potential solution.

The digital market is only just beginning, but...

When I look into the future of the graphic arts industry in Africa, I am convinced that there is great potential, especially with regard to textbooks and other softcover products. The digital market, on the other hand, is still in its infancy, but I see good opportunities for flexible systems that can personalize and produce smaller batch sizes instead of millions. However, if you want to be successful in this segment, you have to focus on the market launch. But unfortunately, there is often a lack of good technical employees in the companies.

In this respect, my two successors in Africa, Alexander Kraitsch (responsible for South and East Africa) and Enrico Farinacci (responsible for North and West Africa), face an exciting task. Over the past few months, the three of us have visited many customers. The transfer of know-how went perfectly. This was particularly important because I am also responsible for all accounting matters in the African market.

1995 to 2005 – the golden years of print finishing

If I have remained loyal to Muller Martini for the last 29 years, it has a lot to do with the special flair of the family business. I feel like a small businessman and appreciate the collegial, family style of working that allows for innovation. The management level is not aloof, but there is a good communication culture across the company.

And during my long career, I have seen Muller Martini launch numerous innovative machines for the most diverse areas of print finishing, always pushing the technical envelope. For example, I remember the ingenious Supra saddle stitcher with 40,000 cycles per hour, launched at drupa 1995, as a particularly great success – or the Avanti log stacker for web presses and the Prima saddle stitcher, which has become a bestseller. The period from 1995 to 2005 were the golden years of print finishing anyway. I am also impressed by the quantum leap with our Finishing 4.0 solutions for digital print shops.

My six drupas between 1995 and 2016 were also exciting. I always enjoyed this high-level performance show. However, it demanded a lot of you physically and mentally – so I won't miss the long days (and evenings!) in Düsseldorf.

I will miss the decreasing contacts, the trips to the airport less

When I look back on my professional life, I'm satisfied with what I've achieved and where I'm at. Of course, sometimes in the evenings or especially in the weeks before retirement, you think about whether you could have done one thing or another differently or better. But I don't have the feeling that I've missed out on anything.

Numerous goals, dreams and plans came true, and I saw (and experienced) a lot in the course of my professional life, especially geographically. I had the privilege of meeting a technically demanding and challenging environment and countless interesting people. I will definitely miss the diminishing contacts from my professional environment (colleagues, agents, customers) in the future – in contrast to the trips to the airport, the check-in, the security checks and the endless waiting times.

What makes the graphic arts industry so appealing

What makes the graphic arts industry so appealing

In the graphic arts industry, I was always attracted to the breadth of applications – from IT networks to mechanics, from chemistry to engineering, from ink to paper. And today, a lot of people are talking about book-of-one. I think it's cool to be a part of that. Of course, there were downsides. For example, despite a lot of effort, I've lost a project now and then – but that's part of a salesman's life…

There's no doubt that the graphic arts industry in general and print products in particular are under pressure – not only because of electronic competition, but more recently also because of high energy and paper prices and the lack of human resources (read: shortage of skilled workers). But in the book sector in particular, which has experienced a major upswing in the past two years, I also see great potential in the long term. Keywords here are haptics, refinement, niches, deceleration, screen fatigue.

For example, I only read books in print – just like the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, to which I have subscribed for many years. Electronically, I only read top news and travel reports (because they convey a live atmosphere in combination with moving images) or when I'm looking for something.

Finally more private travel

Now I'm looking forward to the third phase of my life – especially to the free available time that I can plan myself and that is not dictated by Outlook. But I also have respect. Until now, a lot of things came from the outside; now I have to organize my daily structure myself. I don't have the feeling that I have to make up for something I missed. But I would like to take a few more leisurely private trips rather than hectic professional ones – not by plane, but by motor home. So for this year, together with my wife, I am planning two tours of several weeks on the Iberian Peninsula and on Iceland. And of course, as a grandfather of three, more frequent grandchild herding is the order of the day.

Yours,

Jules Dietz

Would you also like a career at Muller Martini? Here you will find all open positions!